When democracy was placed on pause in India

United Archives through Getty Pictures

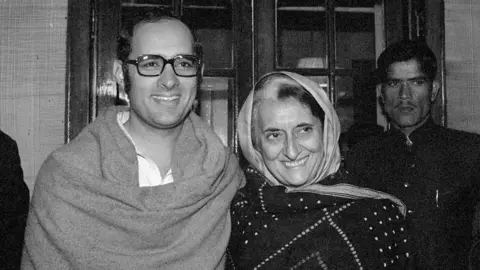

United Archives through Getty PicturesAt midnight on 25 June 1975, India – a younger democracy and the world’s largest – froze.

Then prime minister Indira Gandhi had simply declared a nationwide Emergency. Civil liberties have been suspended, opposition leaders jailed, the press gagged, and the structure became a software of absolute govt energy. For the following 21 months, India was technically nonetheless a democracy however functioned like something however.

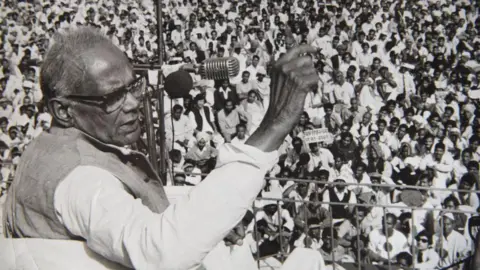

The set off? A bombshell verdict by the Allahabad Excessive Court docket had discovered Gandhi responsible of electoral malpractice and invalidated her 1971 election win. Going through political disqualification and a rising wave of avenue protests led by veteran socialist chief Jayaprakash Narayan, Gandhi selected to declare an “inner emergency” beneath Article 352 of the structure, citing threats to nationwide stability.

As historian Srinath Raghavan notes in his new e-book on Indira Gandhi, the structure did enable wide-ranging powers throughout an Emergency. However what adopted was “extraordinary and unprecedented strengthening of govt energy… untrammelled by judicial scrutiny”.

Over 110,000 folks have been arrested, together with main opposition political figures corresponding to Morarji Desai, Jyoti Basu and LK Advani. Bans have been slapped on teams from the right-wing to the far-left. Prisons have been overcrowded and torture was routine.

The courts, stripped of independence, provided little resistance. In Uttar Pradesh, which jailed the very best variety of detainees, not a single detention order was overturned. “No citizen might transfer the courts for enforcement of their basic rights,” writes Raghavan.

Throughout a controversial household planning marketing campaign, an estimated 11 million Indians have been sterilised – many by coercion. Although formally state-run, the programme was extensively believed to be orchestrated by Sanjay Gandhi, the unelected son of Indira Gandhi. Many consider a shadowy second authorities, led by Sanjay, wielded unchecked energy behind the scenes.

The poor have been hit hardest. Money incentives for surgical procedure usually equalled a month’s revenue or extra. In a single Delhi neighbourhood close to the Uttar Pradesh border – derisively dubbed “Castration Colony” (locations the place pressured sterilisation programmes occurred) – ladies reportedly stated they’d been made bewas (widows) by the state as “our males are not males”. Police in Uttar Pradesh alone recorded over 240 violent incidents tied to the programme.

Of their e-book on Delhi beneath Emergency, civil-rights activist John Dayal and journalist Ajoy Bose wrote that officers have been beneath intense stress to fulfill sterilisation quotas. Junior officers enforced the order ruthlessly – contract labourers have been informed, “No advances, no jobs, until you get vasectomies.”

Getty Pictures

Getty PicturesParallel to this, a large city “clean-up” demolished almost 120,000 slums, displacing some 700,000 folks in Delhi alone, as a part of a gentrification marketing campaign described by critics as social cleaning. These folks have been dumped into new “resettlement colonies” distant from their workplaces.

One of many worst episodes of slum demolitions occurred in Delhi’s Turkman Gate, a Muslim-majority neighbourhood, the place police fired on protesters resisting demolition, killing no less than six and displacing 1000’s.

The press was silenced in a single day. On the eve of the Emergency, energy to newspaper presses in Delhi was reduce. By morning, censorship was regulation.

When The Indian Categorical newspaper lastly printed its 28 June version – delayed by an influence outage – it left a clean area the place its editorial ought to have been. The Statesman adopted swimsuit, printing clean columns to sign censorship. Even The Nationwide Herald, based by India’s first prime minister and Indira Gandhi’s father Jawaharlal Nehru, quietly dropped its masthead slogan: “Freedom is in peril, defend it with all of your may.” Shankar’s Weekly, a satirical journal recognized for its cartoons, shut down solely.

In her e-book – a private historical past of the Emergency – journalist Coomi Kapoor reveals the extent of media censorship via detailed examples of blackout orders.

These included bans on reporting or photographing slum demolitions in Delhi, situations in a maximum-security Tihar Jail, and developments in opposition-ruled states like Tamil Nadu. Protection of the household planning drive was tightly managed – no “adversarial feedback or editorials” have been permitted. Even tales deemed trivial or embarrassing have been scrubbed: no “sensational” reporting on a infamous bandit and no point out of a Bollywood actress caught shoplifting in London.

Kapoor additionally notes that BBC’s Mark Tully, together with journalists from The Instances, Newsweek and The Every day Telegraph, got 24 hours to depart India for refusing to signal a “censorship settlement”. (Years after the Emergency, when Gandhi was again in energy, Tully launched her to the BBC’s chief. He requested the way it felt to lose public help. She smiled and stated, “I by no means misplaced the help of the folks, solely the folks have been misled by rumours, lots of which have been unfold by the BBC.”)

Some judges pushed again. The Bombay and Gujarat excessive courts warned that censorship could not be used to “brainwash the general public”. However that resistance was rapidly drowned out.

Keystone/Getty Pictures

Keystone/Getty PicturesThat wasn’t all. In July 1976, Sanjay Gandhi pushed the Youth Congress – the governing Congress social gathering’s youth wing – to undertake his private five-point programme, together with household planning, tree plantation, refusal of dowry, promotion of grownup literacy and abolition of caste.

Congress president DK Barooah instructed all state and native committees to implement Sanjay’s 5 factors alongside the federal government’s official 20-point programme, successfully merging state coverage with Sanjay’s private campaign.

Anthropologist Emma Tarlo, writer of a richly detailed ethnographic work of the interval, wrote that throughout the Emergency, the poor have been subjected to “pressured decisions”. It was additionally a turning level for industrial relations.

“The final vestiges of working-class politics have been imperiously worn out,” wrote Christophe Jaffrelot and Pratinav Anil of their e-book on the interval they name “India’s first dictatorship”. Round 2,000 commerce union leaders and members have been jailed, strikes have been banned and employee advantages have been slashed.

The variety of man-days misplaced to stoppages plunged – from 33.6 million in 1974 to only 2.8 million in 1976. Strikers dropped from 2.7 million to half one million. The federal government additionally loosened its grip on the non-public sector, serving to the financial system rebound after years of stagnation. Industrialist JRD Tata praised the regime’s “refreshingly pragmatic and result-oriented method”.

Regardless of its heavy-handedness, the Emergency was seen by some as a interval of order and effectivity. Inder Malhotra, a journalist, wrote that in “its preliminary months no less than, the Emergency restored to India a type of calm it had not recognized for years”.

Trains ran on time, strikes vanished, manufacturing rose, crime fell, and costs dropped after a superb 1975 monsoon – bringing much-needed stability. “One reality is conclusive proof of the quiescence of the center class – that hardly any officers resigned in protest towards the Emergency,” writes historian Ramachandra Guha in his e-book India After Gandhi.

Sondeep Shankar/Getty Pictures

Sondeep Shankar/Getty PicturesStudents consider the Emergency’s harshest measures have been largely confined to northern India as a result of southern states had stronger regional events and extra resilient civil societies that restricted central overreach. Gandhi’s Congress social gathering, which dominated federally, had weaker management within the south, giving regional leaders better autonomy to withstand or reasonable draconian insurance policies.

The Emergency formally resulted in March 1977 after Gandhi referred to as elections – and misplaced. The brand new Janata authorities – a rag-tag coalition of events – rolled again most of the legal guidelines she’d handed. However the deeper injury was executed. As many historians have written, the Emergency revealed how simply democratic constructions could possibly be hollowed out from inside – even legally.

“It’s no surprise that the Emergency is remembered emotively in India… Indira’s suspension of constitutional rights seems as an abrupt disavowal of the liberal-democratic spirit that animated Nehru and different nationalist leaders who based India as a constitutional republic in 1950,” historian Gyan Prakash wrote in his e-book on the Emergency.

At this time, the Emergency is remembered in India as a quick authoritarian interlude – an aberration. However that framing, warns Prakash, breeds “a smug confidence within the current”.

“It tells us that the previous is admittedly previous, it’s over, it’s historical past. The current is free from its burdens. India’s democracy, we’re informed, heroically recovered from Indira’s transient misadventure with no lasting injury and with no enduring, unaddressed issues in its functioning,” Prakash writes.

“Underlying it’s an impoverished conception of democracy, one which regards it solely by way of sure types and procedures.”

In different phrases, this notion ignores how fragile democracy might be when establishments fail to carry energy to account.

The Emergency was additionally a stark warning towards the perils of hero worship – one thing embodied within the towering political persona of Indira Gandhi.

Again in 1949, BR Ambedkar, architect of the structure, cautioned Indians towards surrendering their freedoms to a “nice chief”.

Bhakti (devotion), he stated, was acceptable in faith – however in politics, it was “a positive street to degradation and eventual dictatorship”.