The forgotten story of India’s brush with presidential rule

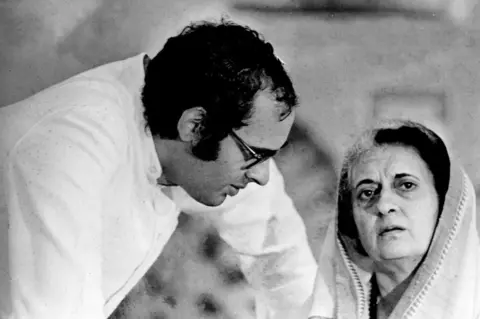

Sondeep Shankar/Getty Photographs

Sondeep Shankar/Getty PhotographsIn the course of the mid-Nineteen Seventies, below Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s imposition of the Emergency, India entered a interval the place civil liberties had been suspended and far of the political opposition was jailed.

Behind this authoritarian curtain, her Congress occasion authorities quietly started reimagining the nation – not as a democracy rooted in checks and balances, however as a centralised state ruled by command and management, historian Srinath Raghavan reveals in his new e book.

In Indira Gandhi and the Years That Remodeled India, Prof Raghavan reveals how Gandhi’s prime bureaucrats and occasion loyalists started pushing for a presidential system – one that may centralise govt energy, sideline an “obstructionist” judiciary and scale back parliament to a symbolic refrain.

Impressed partly by Charles de Gaulle’s France, the push for a stronger presidency in India mirrored a transparent ambition to maneuver past the constraints of parliamentary democracy – even when it by no means absolutely materialised.

All of it started, writes Prof Raghavan, in September 1975, when BK Nehru, a seasoned diplomat and a detailed aide of Gandhi, wrote a letter hailing the Emergency as a “tour de pressure of immense braveness and energy produced by in style assist” and urged Gandhi to grab the second.

Parliamentary democracy had “not been in a position to present the reply to our wants”, Nehru wrote. On this system the chief was repeatedly depending on the assist of an elected legislature “which is on the lookout for reputation and stops any disagreeable measure”.

What India wanted, Nehru mentioned, was a immediately elected president – free of parliamentary dependence and able to taking “robust, disagreeable and unpopular selections” within the nationwide curiosity, Prof Raghavan writes.

The mannequin he pointed to was de Gaulle’s France – concentrating energy in a robust presidency. Nehru imagined a single, seven-year presidential time period, proportional illustration in Parliament and state legislatures, a judiciary with curtailed powers and a press reined in by strict libel legal guidelines. He even proposed stripping elementary rights – proper to equality or freedom of speech, for instance – of their justiciability.

Nehru urged Indira Gandhi to “make these elementary adjustments within the Structure now when you have got two-thirds majority”. His concepts had been “acquired with rapture” by the prime minister’s secretary PN Dhar. Gandhi then gave Nehru approval to debate these concepts along with her occasion leaders however mentioned “very clearly and emphatically” that he shouldn’t convey the impression that that they had the stamp of her approval.

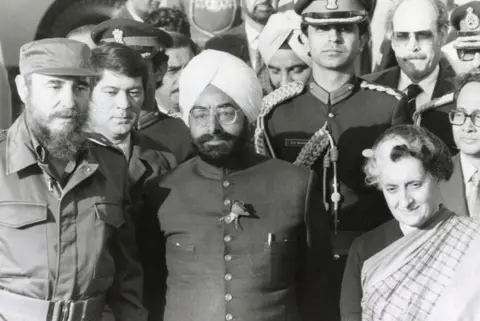

Sondeep Shankar/Getty Photographs

Sondeep Shankar/Getty PhotographsProf Raghavan writes that the concepts met with enthusiastic assist from senior Congress leaders like Jagjivan Ram and overseas minister Swaran Singh. The chief minister of Haryana state was blunt: “Eliminate this election nonsense. In the event you ask me simply make our sister [Indira Gandhi] President for all times and there is no have to do anything”. M Karunanidhi of Tamil Nadu – certainly one of two non-Congress chief ministers consulted – was unimpressed.

When Nehru reported again to Gandhi, she remained non-committal, Prof Raghavan writes. She instructed her closest aides to discover the proposals additional.

What emerged was a doc titled “A Contemporary Have a look at Our Structure: Some strategies”, drafted in secrecy and circulated amongst trusted advisors. It proposed a president with powers larger than even their American counterpart, together with management over judicial appointments and laws. A brand new “Superior Council of Judiciary”, chaired by the president, would interpret “legal guidelines and the Structure” – successfully neutering the Supreme Courtroom.

Gandhi despatched this doc to Dhar, who recognised it “twisted the Structure in an ambiguously authoritarian route”. Congress president DK Barooah examined the waters by publicly calling for a “thorough re-examination” of the Structure on the occasion’s 1975 annual session.

The thought by no means absolutely crystallised into a proper proposal. However its shadow loomed over the Forty-second Modification Act, handed in 1976, which expanded Parliament’s powers, restricted judicial overview and additional centralised govt authority.

The modification made hanging down legal guidelines tougher by requiring supermajorities of 5 or seven judges, and aimed to dilute the Structure’s ‘fundamental construction doctrine’ that restricted parliament’s energy.

It additionally handed the federal authorities sweeping authority to deploy armed forces in states, declare region-specific Emergencies, and lengthen President’s Rule – direct federal rule – from six months to a yr. It additionally put election disputes out of the judiciary’s attain.

This was not but a presidential system, nevertheless it carried its genetic imprint – a strong govt, marginalised judiciary and weakened checks and balances. The Statesman newspaper warned that “by one certain stroke, the modification tilts the constitutional stability in favour of the parliament.”

Sondeep Shankar/Getty Photographs

Sondeep Shankar/Getty PhotographsIn the meantime, Gandhi’s loyalists had been going all in. Defence minister Bansi Lal urged “lifelong energy” for her as prime minister, whereas Congress members within the northern states of Haryana, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh unanimously referred to as for a brand new constituent meeting in October 1976.

“The prime minister was shocked. She determined to snub these strikes and hasten the passage of the modification invoice within the parliament,” writes Prof Raghavan.

By December 1976, the invoice had been handed by each homes of parliament and ratified by 13 state legislatures and signed into regulation by the president.

After Gandhi’s shock defeat in 1977, the short-lived Janata Get together – a patchwork of anti-Gandhi forces – moved shortly to undo the harm. By the Forty-third and Forty-fourth Amendments, it rolled again key elements of the Forty Second, scrapping authoritarian provisions and restoring democratic checks and balances.

Gandhi was swept again to energy in January 1980, after the Janata Get together authorities collapsed on account of inner divisions and management struggles. Curiously, two years later, distinguished voices within the occasion once more mooted the concept of a presidential system.

In 1982, with President Sanjiva Reddy’s time period ending, Gandhi severely thought-about stepping down as prime minister to develop into president of India.

Her principal secretary later revealed she was “very severe” in regards to the transfer. She was bored with carrying the Congress occasion on her again and noticed the presidency as a solution to ship a “shock therapy to her occasion, thereby giving it a brand new stimulus”.

Finally, she backed down. As a substitute, she elevated Zail Singh, her loyal dwelling minister, to the presidency.

Regardless of severe flirtation, India by no means made the leap to a presidential system. Did Gandhi, a deeply tactical politician, maintain herself again ? Or was there no nationwide urge for food for radical change and India’s parliamentary system proved sticky?

Gamma-Rapho through Getty Photographs

Gamma-Rapho through Getty PhotographsThere was a touch of presidential drift within the early Nineteen Seventies, as India’s parliamentary democracy – particularly after 1967 – grew extra aggressive and unstable, marked by fragile coalitions, in response to Prof Raghavan. Round this time, voices started suggesting {that a} presidential system may swimsuit India higher. The Emergency grew to become the second when these concepts crystallised into severe political considering.

“The purpose was to reshape the system in ways in which instantly strengthened her maintain on energy. There was no grand long-term design – many of the lasting penalties of her [Gandhi’s] rule had been probably unintended,” Prof Raghavan advised the BBC.

“In the course of the Emergency, her main objective was short-term: to defend her workplace from any problem. The Forty Second Modification was crafted to make sure that even the judiciary could not stand in her means.”

The itch for a presidential system throughout the Congress by no means fairly light. As late as April 1984, senior minister Vasant Sathe launched a nationwide debate advocating a shift to presidential governance – even whereas in energy.

However six months later, Indira Gandhi was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards in Delhi, and along with her, the dialog abruptly died. India stayed a parliamentary democracy.